Amaranth has been around for thousands of years, but it’s making waves today as a “superfood” among various health communities.

There is a lot of hype surrounding this humble Central American plant, and even more questions.

Let’s cut to the chase. Should amaranth have a place in a healthy diet? Is it Paleo? Here’s what you need to know.

What Is It?

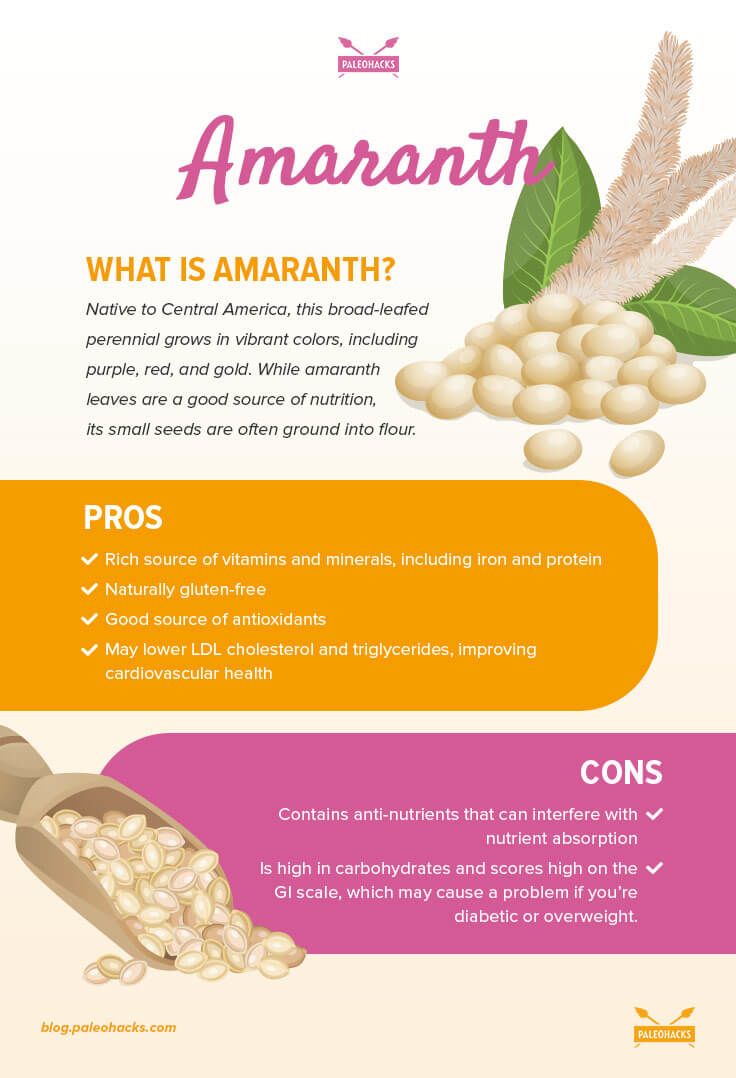

Amaranth is any plant from the genus Amaranthus, which contains over 60 different species and is native to Central America. While many Amaranth varieties are seen as annoying weeds, several are cultivated as food crops.

The amaranth plant is a tall (approximately six feet), broad-leafed perennial, favorable to moist, loose soil. Its leaves grow in vibrant colors, including purple, red, and gold. Although amaranth leaves are edible and a good nutrition source in their own right, many people harvest the small seeds which grow on the plants (up to 60,000 per plant) and eat them either whole or ground into flour. [tweet_quote] Amaranth is a vibrantly colored plant, and both its seeds and leaves are edible.[/tweet_quote]

Amaranth was a staple of the ancient Aztecs, who also used the seeds in religious ceremonies. When Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors landed in modern-day Mexico, they outlawed the plant, burning crops and punishing whoever had them in their possession due to their link to “pagan practices” (1).

Despite Cortés’ best efforts, the amaranth plant persevered. Today it is grown far and wide, everywhere from Africa and Asia to South America and even the United States.

Why Amaranth Isn’t a Grain

For Paleo enthusiasts, amaranth presents a bit of a mystery.

You’ve probably heard it lumped in with cereal grains like wheat. Because you know those can cause health issues, it’s easy to overlook amaranth as an option. Amaranth looks like a grain, is used like a grain, and is often categorized as such, so wouldn’t we be better off simply avoiding it?

The truth is murkier than you might expect.

In reality, amaranth isn’t a grain at all. The amaranth most people refer to is the amaranth seed, which is sometimes ground into flour. Amaranth falls within the order Caryophyllales, making them relatives of cacti, beets, and carnations (2). True cereal grains, like wheat and rye, come from the family Poaceae and are the seeds of grasses. [tweet_quote] Amaranth isn’t a grain — it’s a seed, which makes it Paleo-friendly.[/tweet_quote]

This puts amaranth into that gray area of “pseudograins.” Many Paleo enthusiasts consider it technically non-Paleo. Like quinoa and buckwheat, amaranth isn’t related to cereal grains. But it’s often used like cereal, so people consider it as such.

That raises a few questions. Should we be eating this pseudograin? What effects does it have on our health, and are they any different from cereal grains?

Amaranth Health Benefits

Let’s start off with the pros of making amaranth a part of your diet. As you’ll see below, there are some key differences between it and typical cereal grains that might make it worth a look.

Good Nutrient Profile (with a Few Caveats)

Amaranth is a rich source of vitamins and minerals, as well as the amino acid lysine. It also contains more protein than you might expect.

Just one cup of cooked amaranth (250 calories) contains:

- 105 percent of the daily value of manganese

- 40 percent of the daily value of magnesium

- 36 percent of the daily value of phosphorous

- 29 percent of the daily value of iron

- 19 percent of the daily value of selenium

- 18 percent of the daily value of copper

- 14 percent of the daily value of vitamin B6

- 9.3 grams of protein (3)

While these numbers aren’t anything to sniff at, it takes adequate preparation to ensure the nutrients are as bioavailable as possible. As a pseudograin, amaranth contains some anti-nutrients, like saponins and tannins, which can interfere with nutrient absorption and cause other issues without adequate preparation. More on those in just a bit.

Amaranth offers more nutrients than cereal grains, but retains a similar carbohydrate content. That same cup of amaranth contains 46 grams of carbohydrates, so if you’re overweight, out of shape, or in poor health, be sure to limit portion sizes or skip it. Researchers also found it’s high on the glycemic index (GI), which means it’s processed quickly in the body and might cause issues for diabetics or those with blood sugar control issues (4).

Gluten-Free

Gluten is public enemy number one in many health communities. It’s the protein composite found in many grains, giving dough its elasticity and making baked goods chewy. But it damages the gut lining and can be a digestive nightmare for those who are gluten intolerant or have been diagnosed with Celiac disease (5).

With amaranth, there’s no gluten to worry about. Because it isn’t a grain at all, but a seed, it’s naturally gluten-free.

Antioxidant Effects

Numerous studies have explored amaranth’s antioxidant abilities and came to some interesting conclusions. Research published in the journal Food Research International scrutinized peptides (compounds consisting of two or more linked amino acids) found in amaranth proteins. The researchers observed that multiple peptides had a free radical scavenging effect (6).

[tweet_quote] Both amaranth seeds and sprouts are good sources of antioxidants.[/tweet_quote]

Another study published in Food Chemistry supported those findings. Researchers examined the total antioxidant capacity of amaranth seeds and sprouts. They concluded that both forms could be used in food because they were a good source of anthocyanins and phenols, known antioxidants (7).

May Lower LDL Cholesterol and Triglycerides

A lot more research needs to be done here, but some animal and human studies suggest amaranth might be good for your heart.

A study published in Food Chemistry investigated amaranth’s protein cholesterol-lowering effect on hamsters. Researchers divided hamsters into three groups: the first received casein protein, the second received amaranth, and the third got a blend of the two. After four weeks, the groups that received amaranth and the blend reduced LDL cholesterol significantly (8). Another hamster study used amaranth oil and noted similar effects (9).

Why? Researchers at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, discovered amaranth is a rich source of phytosterols, which have a known cholesterol-lowering effect (10).

Russian researchers explored the effect on humans with cardiovascular disease. They found that patients who added amaranth to their diets experienced significant decreases in LDL cholesterol and triglycerides (11).

What About Anti-Nutrients?

Because amaranth seeds can’t just hop up and run away from predators, it’s only natural they’ve developed defenses against being eaten. These “anti-nutrients” can limit mineral absorption and may increase intestinal permeability, causing digestive problems and contributing to a leaky gut.

Saponins are compounds that can potentially damage the cells lining your intestines. Too many of them can punch little holes in your intestines, allowing toxins and bacteria to slip through into your bloodstream (12). While amaranth does contain saponins, one study found they only accounted for .09 to .1 percent of the total dry matter (13). The researchers concluded that low saponin content and toxicity created “no significant hazard for the consumer.” [tweet_quote] Amaranth has few anti-nutrients to begin with, and soaking them can help minimize them even more.[/tweet_quote]

Additional preparation minimizes anti-nutrients, but won’t eliminate them completely. Traditional methods, like soaking them in water and waiting for seeds to sprout, work best. Kenyan researchers soaked amaranth seeds and let them germinate afterward in an attempt to find the optimal processing time (the time which minimized anti-nutrients and maximized nutrients). They concluded that a five-hour soaking time, followed by 24 hours of sprouting, was ideal (14).

Once you soak amaranth seeds and sprout them, cooking them further degrades the anti-nutrient content. A study published in the journal Food Science and Quality Management found that boiling or dry heating amaranth significantly decreased anti-nutrients (tannins, oxalates, and phytates) while increasing protein digestibility (15). Because cooking degrades the vast majority of anti-nutrients, you won’t destroy your gut health by having the occasional serving.

How to Use Amaranth

You can consume amaranth in several different forms: plant leaves, seeds, or seed flour.

Amaranth leaves taste a bit like spinach. You can eat them raw in salads, or even stir-fry or saute them. Amaranth leaves are popular in Asian and African dishes. The leaves are rich in vitamin C, vitamin A, manganese, and calcium (16).

The most popular form of consumption is the seeds themselves, which are easy to boil. Preparation is similar to cereal grains, but use a lot of water. Six cups of water per cup of amaranth seeds is a good ratio. Just bring the water to a boil, add the seeds, stir gently for 15 to 20 minutes, drain and enjoy. It has a nice, nutty flavor and a porridge-like texture. [tweet_quote] Love crunchy foods? Try warming amaranth seeds. They’ll pop just like popcorn![/tweet_quote]

For a crunchier experience, you can also pop amaranth seeds like popcorn. Just heat up a skillet, sprinkle the seeds onto a pan, and stir with a wooden spoon until they start popping. You can find amaranth seeds at most grocery stores, with the best selection being at more upscale places like Whole Foods. If you prefer to buy in bulk, there are tons of options online.

Amaranth flour opens up a world of baking possibilities. It’s a way to avoid gluten while still enjoying some of your favorite baked treats or bread. If you’re used to cooking with wheat flour and haven’t experimented with gluten-free alternatives (like almond or coconut flour), it might take some tweaking of your recipes because amaranth flour is less elastic.

The Bottom Line

Amaranth is a more nutritious, gluten-free alternative to inferior cereal grains. Prepared properly to minimize the anti-nutrients, amaranth offers a grain-like experience without as many negative health effects.

Consider why you’re avoiding grains in the first place. If you have trouble with gluten, but are physically active and tolerate other carbohydrate sources well, it might be fine to have amaranth occasionally. But if you’re mostly sedentary, have elevated blood sugar, or want to cut carbs and lose weight, you’re better off sticking to the Paleo basics. You might find that the amount of prep work involved drives you to opt for more convenient carbohydrate sources, like sweet potatoes.

What are your thoughts on amaranth? How about “pseudograins” in general? Leave a comment below and let us know!

Paleo Eggnog Recipe

Paleo Eggnog Recipe

Show Comments