Chocolate, bread, pizza, candy…

What was once a favorite treat or a prized meal is now off-limits. Cravings are inevitable.

If you’re one of those rare people who crave carrot sticks, there’s no problem. But for most folks, dealing with cravings is a huge part of life, whether you eat Paleo or not.

Want to train your brain to be happier and healthier?

Click here to receive our FREE 7-Day Meditation Challenge!

I’m going to break down the science behind cravings so we can get some answers.

I’ll give you one spoiler up front – if someone tells you that you just need more willpower, they’re barking up the wrong tree.

We All Crave the Same Foods (More or Less)

When you get hungry, you crave food, but this is different from having a craving.

A craving is defined as a desire for a specific food or selection of foods, but not just food in general [1].

Even though we are all unique in ways, we’re also scarily the same in other ways.

When large groups of people are studied, their most common cravings are always the same [2]. Here’s a great infographic that breaks down the common cravings:

What do you notice?

People crave foods that taste good (are highly palatable). Chocolate, salty snacks, foods with additives like MSG, and pizza are all loved by a large majority of the population.

There’s a common myth that people crave foods with nutrients (vitamins and minerals) that they need. The human body is smart, but not that smart. Other than a rare condition called Pica, cravings have nothing to do with wanting specific nutrient [3]. Otherwise, people would crave nutritious foods like spinach much more.

The 3 True Underlying Causes of Most Cravings

Part of the reason there is a lot of muddled results from studies about cravings is because they can be caused by so many different things.

I’ve gone through the most comprehensive studies I could find, and it turns out there are 3 factors that seem to be the most important (by far).

Cause #1: Emotion

I don’t think it’s a shock to anyone when I say that humans, despite valiant efforts by some, are not logical creatures.

We try to make good decisions, and often succeed, but those emotional choices we make often lead to bad decisions. This isn’t limited to just eating choices, either.

Getting back to the topic at hand, many studies have revealed that emotions play a key part in when we start to crave for foods. Cravings have been linked to:

- Boredom

- Anxiety

- Stress

- Sadness

- Guilt

Important note: Emotions vary widely from person to person. Boredom causes cravings in some, but not in others. There are even some people who experience strong cravings when happy [4].

Why do Emotions Cause Cravings?

The most promising theory so far appears to be reward-based stress eating [5]. The theory is based on the importance of cortisol and other appetite-regulating hormones.

When people get stressed, they release opioids, which are chemicals that relieve pain. It turns out that eating highly palatable foods can also release opioids, which is essentially a reward of eating certain foods. Studies have shown that many cravers feel better after eating what they craved [2][6][7].

It follows, then, that when we experience a negative emotional state, like stress or boredom, we might try to feel better by trying to produce more opioids through eating. It’s possible that the body initiates the craving on its own, or even that they are developed over time as a habit.

Do All Emotions Cause the Same Cravings – No!

Why do we give in to some cravings, but not others?

One of the most interesting findings I came across was that the higher the stress or negative mood, the more likely a person is to give into those cravings, possibly even bingeing [8].

Cause #2: Restriction

Do you like being told what to do?

If someone tells me not to do something, I almost always do it (I’ve also been told I have the maturity level of a child).

While you might not be as stubborn as I am (or maybe you are), the majority of people have an instinct to be free – to make their own choices.

Many studies have looked at the effects of dieting on cravings. Most dieters change what they eat by cutting out “bad foods” like chocolate and junk foods. This can lead to a “boring” and repetitive diet.

This restriction has been shown to increase craving frequency and intensity [9]. One study found that under monotony (a very restrictive diet), cravings quadrupled [10].

The Pink Elephant Craving

When I tell you not to think about a pink elephant, do you think of a pink elephant? This classic example illustrates the second problem with cutting foods out of your diet. The less you can have something, the more you crave it [11].

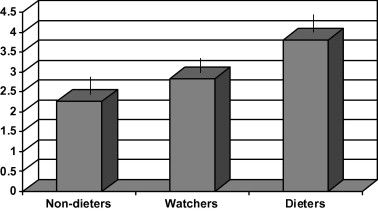

One study took 129 women and split them into 3 groups: one that was dieting, one that was watching their weight, and one that was not dieting at all as a control group.

The picture below shows the cravings of the 3 groups during the study:

Among the 3 groups, dieters experienced the most cravings (about twice as much as non-dieters) [12].

Special Case: Fasting (This Surprised Me)

So if cutting back on food a little increases cravings, fasting must skyrocket them, right?

Upon closer inspection, fasting is a different beast altogether. Instead of cutting out specific foods, you’re cutting out all foods for a set amount of time. And while you might expect some increase in cravings, fasting actually causes a decrease in cravings [13][14]. You might want to learn more about intermittent fasting if you’re having trouble with cravings.

Cause #3: Habits (and Triggers)

Ever trained a pet to do a trick by offering a treat? Over time, your pet will automatically do the trick as the reward enforces the behavior. This is an example of classical conditioning.

Humans can also be conditioned:

- Did your homework? Have a cookie.

- Ate your vegetables? Have dessert.

- Want to watch T.V.? Eat your cereal first.

The specifics don’t matter, but just know that people tend to associate foods with events if they occur enough. Note that this can be related to emotions as well (e.g. going through a breakup? Drown your sorrows in ice cream).

Do You Know Your Triggers?

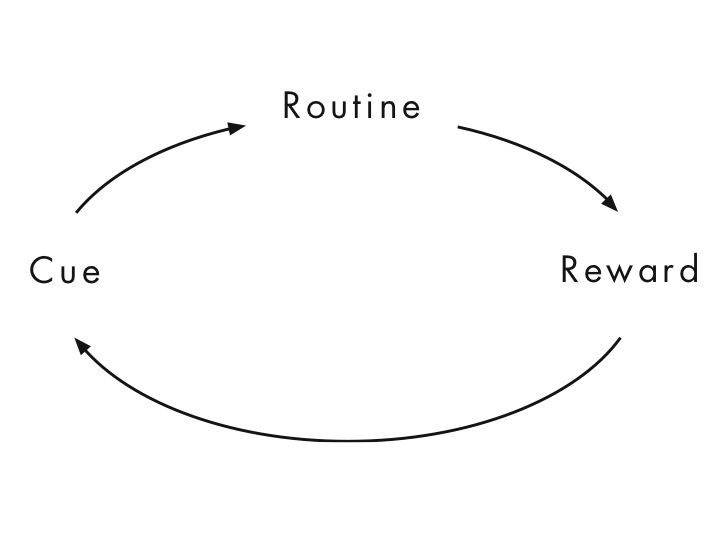

Charles Duhigg, one of the most famous authors on habits, coined the “habit cycle” that is pictured below:

All habits have 3 components: A cue (some call it a trigger), a routine, and a reward.

When we talk about food cravings, the routine is eating, and the reward is the pleasant taste and good feelings. So that leaves the trigger component.

There are a near-infinite amount of triggers in real life, but here are the most common that lead to cravings (and acting on them):

- Thinking about a certain food (the more vivid, the stronger the craving) [15]

- Smelling or seeing foods [16]

- Emotional states (as discussed earlier)

- Events (e.g. dessert after dinner)

Habits can be unlearned, but it is tough.

Ladies, You’re at a Disadvantage…

I can’t say I can relate, but it’s been conclusively shown that women have to deal with some pretty crazy hormone changes during menstruation and pregnancy. These changes cause not only intense cravings, but often some weirdly specific ones as well [17].

Perhaps one of PaleoHack’s awesome women writers can tackle this specific topic in more depth at some point.

Paleo and Cravings

By definition, eating a Paleo diet will involve a lot of restriction. While there are no relevant studies concerning Paleo and cravings, I think it’s logical to say that this factor alone most likely results in extra cravings. This makes the final section of this article even more important.

How to Handle Your Cravings

You understand that cravings are highly personal things, right?

Because of that, I can’t give you a blanket solution. What I can do, however, is give you a variety of solutions for different problems that cause cravings, and you can pick and choose which ones you think will help.

Option 1: Restricting Foods? Change Your Perspective

I believe this is the most important thing that anyone trying to eat better can do.

Restricting foods is a good thing, as long as it doesn’t cause you to crave excessively and end up bingeing, which is bad for your mental and physical health.

But instead of thinking of it as: “I can’t eat bread anymore,” think of it as “I can eat bread, but I’m choosing not to in order to be healthier.”

And that’s a very simplistic example, but you can start with that and tailor it to your own personal situation.

To make it even more effective, instead of saying something general like “…to be healthier,” think of it in terms of the benefits you’ll receive. For example:

- …to have more energy

- …to lose weight and feel more confident

- …to be sick less often

- etc.

If you have extreme issues with negative thinking and cravings, you may want to seek professional help from a therapist. There have been great results shown from using cognitive behavioral modification techniques to reduce cravings [18][19].

Option 2: Diet Change? Wait it Out

If you are new to Paleo and are coming from a drastically different diet, you are going to have more cravings than normal. It’s unavoidable, in many ways comparable to withdrawal that addicts face when trying to quit.

However, the bright side is that the cravings will subside in time. One particularly interesting study showed that cravings decrease over time as you adjust to a new diet, and low-carbohydrate (like Paleo can be) diets are easier to get used to [20].

Option 3: Break or Hijack a Bad Habit

If you know that your cravings are a result of bad habits, you have no other choice but to try and break them, one at a time.

You can either try to break them altogether, or try to replace the “routine” (food being eaten) with a different one, which is often easier.

Long story short, to hijack a habit when you crave a certain food, replace it with a healthy alternative. Each time you do this, a little bit of the craving will be transferred to that new food, until the habit is completely reformed.

Option 4: Compromise/Find a Paleo-Friendly Alternative

Chocolate is the most common craving by far, but does it need to be eliminated from your diet?

There’s definitely a grey area when it comes to cocoa, but most Paleo practitioners are fine with including some in their diet as long as it has no other questionable ingredients.

If you are craving chocolate, have a square or two of dark chocolate (the darker the better). This can eliminate the craving before it gets out of hand and causes you to eat too much.

Many people who eat Paleo think it’s a “boring” diet, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. There are a ton of awesome recipes on the PaleoHacks blog that you can experiment with and many Paleo snacks to help fight cravings. Yes it’s more work than ordering a pizza, but think about why you started eating Paleo in the first place – the benefits are worth a little effort.

Option 5: Exercise or Distraction

What do you do when you are exposed to a trigger and can’t stop thinking of a food?

One option is exercise. A fairly recent study showed that participants had a much lower craving response after exercising [21]. Even a quick 5-minute workout can help keep those cravings at bay.

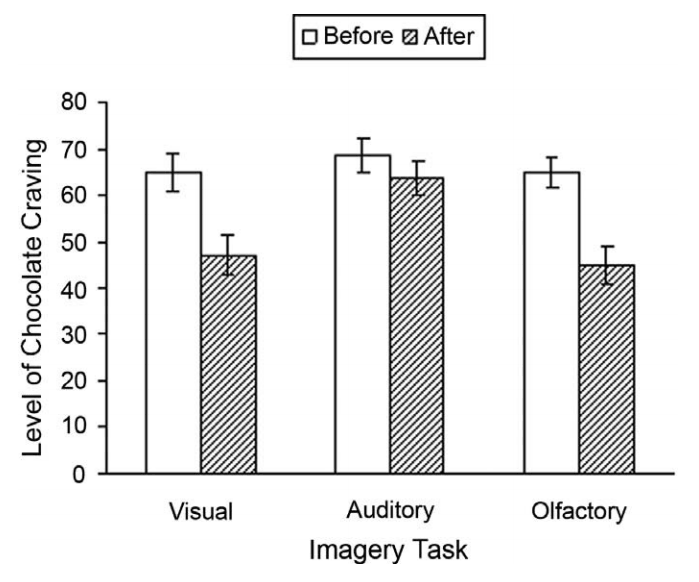

Another option is to distract your mind. While you can’t simply tell your brain to stop thinking about a food, you can get it to think about other things. One study showed that after doing an activity that engaged one of the senses (sight, smell, hearing), the intensity of a craving decreased (see the graph below) [22]:

You could go around smelling other things, or go watch a video. As the graph shows, audio distraction works, but not nearly as well as visual or smelling distraction.

Summing It Up – Cravings in a Nutshell

Experiencing some cravings is normal, as is giving in to them every once in awhile. Don’t feel bad or beat yourself up if you do give in, just keep trying.

If you think you have an issue with cravings, follow this 3-step procedure:

- Write down any cravings you have, as well as when, where, and environmental factors when they occur.

- After a few weeks, analyze your cravings and try to identify the causes of your cravings. See if they fall under one or more of the causes in this article.

- Select appropriate solutions from above and implement them. Track your progress.

If you do those 3 things, you should see marked improvement in the frequency and intensity of your cravings. This will help you achieve the Paleo diet that you’ve been trying to eat.

If you have any experiences with cravings, please share them in the comments below! [author_bio name=”yes” avatar=”yes”]

References

Andrew J. Hill (2007). The psychology of food craving. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 66, pp 277-285. doi:10.1017/S0029665107005502.

Hill AJ & Heaton-Brown L (1994) The experience of food craving: A prospective investigation in healthy women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 38, 801–814.

O’Rourke DE, Quinn JG, Nicholson JO, Gibson HH. Geophagia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1967 Apr;29(4):581-4.

Christensen, L., and L. Pettijohn. “Mood and Carbohydrate Cravings.” Appetite 36.2 (2001): 137-45. Web.

Adam, Tanja C., and Elissa S. Epel. “Stress, Eating and the Reward System.” Physiology & Behavior 91.4 (2007): 449-58. Web.

Macht M & Simons G (2000) Emotions and eating in everyday life. Appetite 35, 65–71.

Macdiarmid JI & Hetherington MM (1995) Mood modulation by food: An exploration of affect and craving in ‘chocolate addicts’. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 34, 129–138.

Waters A, Hill A & Waller G (2001) Bulimics’ responses to food cravings: Is binge-eating a product of hunger or emotional state? Behavior Research and Therapy 39, 877–886.

Pelchat ML & Schaefer S (2000) Dietary monotony and food cravings in young and elderly adults. Physiology and Behavior 68, 353–359

Pelchat ML (2002) Of human bondage: Food craving, obsession, compulsion, and addiction. Physiology and Behavior 76, 347–352.

Herman CP & Polivy J (1993) Mental control of eating: Excitatory and inhibitory food thoughts. In Handbook of Mental Control, pp. 491–505 [DM Wegner and JW Pennebaker, editors]. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Massey, Anna, and Andrew J. Hill. “Dieting and Food Craving. A Descriptive, Quasi-prospective Study.” Appetite 58.3 (2012): 781-85. Web.

Harvey J, Wing RR & Mullen M (1993) Effects on food cravings of a very low calorie diet or a balanced, low calorie diet. Appetite 21, 105–115.

Martin CK, O’Neil PM & Pawlow L (2006) Changes in food cravings during low-calorie and very-low-calorie diets. Obesity 14, 115–121.

Tiggemann M & Kemps E (2005) The phenomenology of food cravings: The role of mental imagery. Appetite 45, 305–313.

Federoff I, Polivy J & Herman CP (2003) The specificity of restrained versus unrestrained eaters’ responses to food cues: General desire to eat, or craving for the cued food? Appetite 41, 7–13.

Dye, L., and J. E. Blundell. “Menstrual Cycle and Appetite Control: Implications for Weight Regulation.” Human Reproduction 12.6 (1997): 1142-151. Web.

Moffitt, Robyn, Grant Brinkworth, Manny Noakes, and Philip Mohr. “A Comparison of Cognitive Restructuring and Cognitive Defusion as Strategies for Resisting a Craved Food.” Psychology & Health 27.Sup2 (2012): 74-90. Web.

Forman, E., K. Hoffman, K. Mcgrath, J. Herbert, L. Brandsma, and M. Lowe. “A Comparison of Acceptance- and Control-based Strategies for Coping with Food Cravings: An Analog Study.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 45.10 (2007): 2372-386. Web.

Martin, Corby K., Diane Rosenbaum, Hongmei Han, Paula J. Geiselman, Holly R. Wyatt, James O. Hill, Carrie Brill, Brooke Bailer, Bernard V. Miller Iii, Rick Stein, Sam Klein, and Gary D. Foster. “Change in Food Cravings, Food Preferences, and Appetite During a Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diet.” Obesity 19.10 (2011): 1963-970. Web.

Evero, N., L. C. Hackett, R. D. Clark, S. Phelan, and T. A. Hagobian. “Aerobic Exercise Reduces Neuronal Responses in Food Reward Brain Regions.” Journal of Applied Physiology 112.9 (2012): 1612-619. Web.

Kemps, E., and M. Tiggemann. “A Cognitive Experimental Approach to Understanding and Reducing Food Cravings.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 19.2 (2010): 86-90. Web.

How To Improve Your Posture and Improve Your Life

How To Improve Your Posture and Improve Your Life

Show Comments